In today’s installment of Feminist Friday, we’re tackling “The Duke” himself, John Wayne. The legendary actor has a long string of movies spanning 40 years, building himself a solid (and unchanging) star persona. John Wayne is John Wayne. In his 1962 film, Hatari, Wayne combines with Howard Hawks to craft a film which is the epitome of an idealized, classic Hollywood masculinity. As such, the movie proves to be a fascinating viewing when looking through a lens of gender and sexuality. Where does all this testosterone leave Hatari‘s female characters.

**Before I begin… I was raised on this movie and absolutely love it. However, this doesn’t change the…problematic parts**

Hatari follows a team of hunters and adventurers tasked with capturing the animals needed by western zoos from the wild’s of Africa. There’s life and love as they traverse the constant specter of death surrounding their action-packed day job. John Wayne stars in the film. He’s backed up by an international cast: Red Buttons, Hardy Krüger, Elsa Martinelli and Valentin de Vargas to simply name a few members of the large team. Howard Hawks directed the film from a script by Leigh Brackett.

Now, the film does have two named female characters: Dallas (Martinelli) and Brandy (Michèle Giradon), and they do have a (albeit fast) conversation about something other then men. However, this minute (and surprising!) passage of the Bechdel Test is about as far as Hatari‘s progressivism goes, unfortunately.

As mentioned above, this movie is the epitome of an idealized, mid-century masculinity (we know in truth, this era was far more complicated). Wayne leads the group of big-game, animal hunters (for lack of a better word) through Africa. There are guns, drinking, lots of camping and…. romance?

While Hawks is well-known for the fascinating female characters he crafted throughout the 1940s in films like His Girl Friday and To Have and To Have Not, by Hatari’s release in June 1962, things changed. As photographer Dallas, Martinelli brings the shell of a candy-coated Hawksian woman. The Italian photographer has no problem dropping everything and relocating to the wilds of Africa to photograph animals. She can “take care of herself”. However, one she arrives, the film takes careful care to show she really can’t play with the boys. This begins immediately as Dallas rides in the back of the truck on her first hunt. The road is so bumpy (and she is such a weak feminine flower) that she is knocked over and must ride the rest of the way on the floor of the truck bed. Thus, the narrative immediately knocks her down a peg… I bet Hildy could have at least held on.

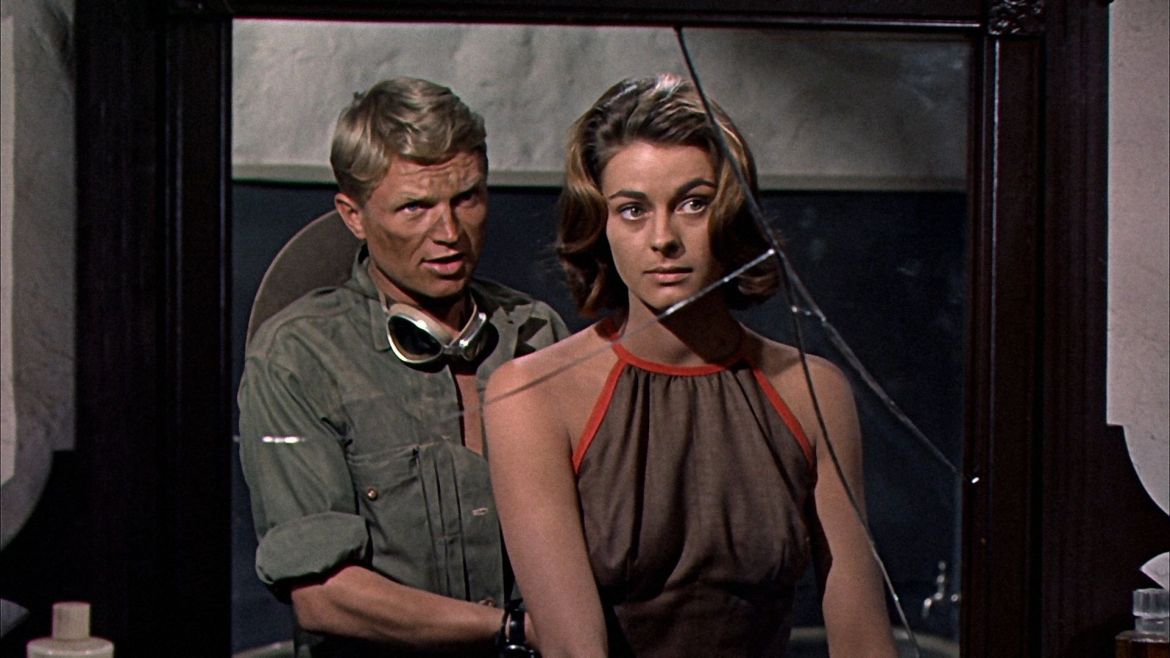

The film showcases an on-going metaphor seemingly comparing women to animals, particularly when developing Dallas. The portrayal morphs as the story progresses. Early in the movie, Dallas is often seen with a cheeta. She herself is sleek, slender and almost cat-like. In fact, in the above picture, she is almost cat-like in how she’s curled up in her chair. The characterization of Dallas feels almost predatory. She’s arrived unexpectedly (they expected her to be a male photographer) and changes the dynamic of the group. However, by the third act, the imagery changes when Dallas adopts three baby elephants. Suddenly, she’s maternal. Even Sean (Wayne) calls her “mother”. It is this development of a maternal characterization which allows her to become an acceptable love interest for Sean. And as such, the film attains its Hollywood standard happy-ending.

Meanwhile, Brandy is held up as a well-respected member of the team. When Dallas speaks with Sean about Brandy, he says, “She was born and raised here. She can drive as well as anyone except Kurt. She can shoot a gun as well as anyone except the Indian”. Almost immediately in this quote, it is evident how femininity is inherently second. While Brandy grew up around the camp, she’s not quite good enough to completely play with the big boys.

In fact, as a character Brandy falls easily into a passive role (as opposed to the slightly more active Dallas). This encompasses not only her role within the team (she drives up to the hunts, but is shown watching as the guys struggle with the animals), but also as a love object.

For much of the movie, Brandy is held as the primary object of desire with Kurt (Krüger), Chips (Blain) and Pockets (Button) at various points each trying to win her over. The romantic arc begins in earnest as Kurt realizes his feelings for Brandy when he helps her fasten her dress. For much of the narrative, the film never bothers to give Brandy’s perspective on things. In fact, she is so passive it’s difficult to ascertain if she even knows the men are fighting over her. She is very much a screen for them to project their desires on.

In fact, Brandy’s personality doesn’t show through until the third act when it becomes clear that not only does Pockets have feelings for her, but she also likes him. The crew learns this when she nurses a (perfectly healthy) Pockets back from perceived injury when he falls off a small fence. However, the narrative (still seeing through Kurt and Sean’s perspective) makes it perfectly clear that nothing is wrong with Pockets. As such, Brandy ends up looking like a fool for falling for his act.

Finally, the romantic narrative swirling around Brandy doesn’t age well when watching the film through contemporary eyes. As mentioned earlier, she’s grown up around the team. At one point, Kurt looks to Sean, “How old is Brandy?”. Sean thinks for a moment, “Well, she was sixteen when…”. Kurt cuts in, “Have you had a good look at her lately?”. Kurt in particularly seems to particularly grapple with her age. Later, after he gives her a gift (which sounds to be of the lingerie variety) he looks to Sean, “She was just thanking Uncle Kurt for giving her a present”. Ewww. While Giradon was roughly 24 at the time of shooting, and Brandy looks to be of legal age, the men don’t seem to think of her that way. Yet, it doesn’t rule her out as a love interest for any number of the “young bucks”.

Hatari is a fascinating film, and serves an important role as a mid-twentieth century time capsule. This movie is very much of its time, and this translates to the depiction the issues of gender and sexuality. While there are definite problems, it’s still a tremendously enjoyable, (albeit long) viewing.

FOLLOW US ON: FACEBOOK, TWITTER