When Jennifer Kent’s follow-up to The Babadook first hit the festival circuit it became a lightning rod for notoriety. Walk-outs were common, with audiences uncomfortable with the first 30 minutes heavy emphasis on rape and violence. And yet, it’d be interesting to see if this same outcry would have been lobbed at a male director? In Kent’s hands, The Nightingale is a brutal story deeply rooted in the history of Tasmanian independence that also examines the toxic masculine culture we’re still seeing evidence of today.

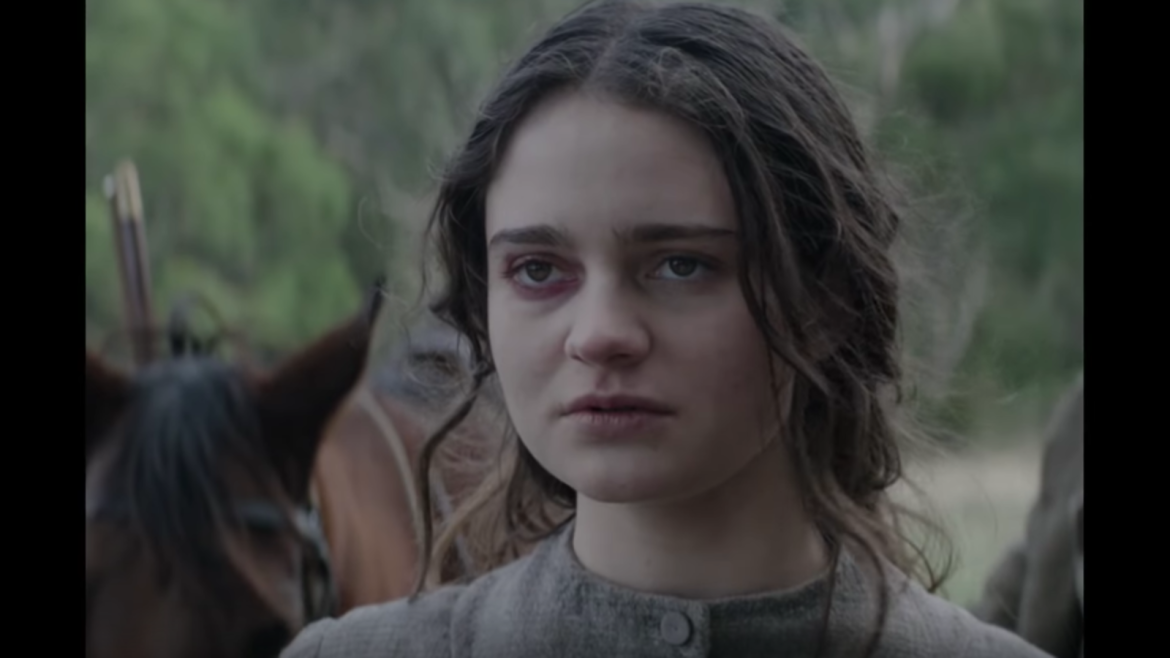

Aisling Franciosi plays Clare, an Irish convict with a husband and baby, but her freedom comes at a price. She remains the “property” of British lieutenant, Hawkins (Sam Claflin), who regularly assaults and degrades her. When Hawkins, in a fit of anger, kills her husband and child Clare goes on a mission of revenge. Helping her along the way is Aboriginal man Billy (Baykali Ganambarr), who’s grievances with the British run deeper than anyone else’s.

Kent, returning as writer and director, tells a story with deep and complicated roots. Where The Babadook examined depression and motherhood, The Nightingale examines the nebulous world of Australian history, colonialism, racism, and degredation of both women and people of color. That’s a lot of broad, complicated topics to fit into a nearly two-and-a-half hour movie, and it’s one of the reasons The Nightingale lacks the staying power of The Babadook. Where that film was firmly in the horror world, The Nightingale’s terrors stem from the sheer horror of being a woman or a person of color throughout history.

Clare is the audience’s starting point, being not only a woman in a landscape hewed out and controlled by men; she’s a convict whose freedom only extends as far as Hawkins is willing to go. Kent perfectly lays out a story of toxicity, misogyny, and fear, but does so in a way that feels so authentic to 2019 despite the time period. Hawkins never claims to love Clare, but he proceeds to find ways to at least make himself believe he cares, giving her little trinkets before violently raping her. For him, she’s his property but if he can convince her to love him, that would just make things easier.

Sam Claflin’s performance isn’t particularly revelatory, if only because we’ve seen characters like him in so many movies before. What helps him stand out is Kent’s writing, which makes him so evil and disgusting, but at the same time you can see his rationalizations. Kent wants to look not just at one relationship, but the systemic world that creates men like Hawkins. Hawkins being berated by his commanding officer forces him to find an outlet to prove he is a man, hence the inciting incident that sets Clare on her quest for revenge. Later, Hawkins takes a shine to a little boy named Eddie (Charlie Shotwell), whom he continually seeks to inspire and goad to “be a man,” which he sees as being able to shoot someone without pity.

The derision against Kent’s film is fascinating because there’s no question that she expects people to feel uncomfortable watching what she’s presenting. We should always question not just the use of rape on-screen but the history of nearly every country that’s been founded on rape and the subjugation of people, which is Kent’s point. Franciosi is a bright talent who conveys the fear, demoralization, and ultimate catharsis that her character goes through but the true scene stealer (both in terms of performance and writing) comes from Ganambarr’s Billy.

As a character Clare acts as a conduit, bridging the gap between the exposition of the white Tasmanians and their subjugation by the English and the Aboriginals whose spate of torment is longer and far more racist. Clare, upon first meeting Billy, finds that her only means of power comes from being racist towards her coerced guide, Billy. She threatens him with a gun and believes the stories that Aboriginals “eat” white people. Kent showcases that, despite how the audience sympathizes with Clare, she’s racist (though considering she is the star there’s always going to be a whiff of white feminism to the movie).

That being said, Billy is written with such sensitivity that’s beautifully balanced out by Ganambarr. He describes the history of his people, and how they’re dying out because of colonialism. At one point an Aboriginal woman is assaulted and kidnapped. Much like Clare she is a pawn in a game played by white men, her life only going so far as they allow it. Kent never plays the game of whose life is worth, simply putting Clare and Billy in the same boat.

Their lives have been shaped, defined, and ruined by British imperialism, though Clare will always be in a position of privilege. When Billy and Clare see a chain gang of Aboriginals Clare is forced to act like Billy is her prisoner to get him through the crowd of white men. Despite their friendship there will always be a remove because of the systemic racism that has defined their heritage.

The Nightingale is as far from The Babadook as it gets which shows Kent’s range as a dramatist. Her work is difficult and dense, as it should be. The cast capably wraps their tongues around her beautiful dialogue, and she compacts such haunting history in a taut package. The Nightingale demonstrates that the most frightening thing in the world is the history that’s formed every country and our ability to repeat it.

The Nightingale hits theaters August 2nd.