*This is a reprint of a paper I wrote for Ed Guerrero’s “Horror, Sci-fi, and Difference” class during my Master’s degree at NYU. Heavy on the academe, but somehow appropriate to our current moment.*

‘Funny us going out like this: killed by a hundred-foot marshmallow man.’ –Ray Stantz (Dan Aykroyd) in Ivan Reitman’s Ghostbusters (Columbia, 1984).

One of the more indelible cinematic images of terror and humor of the late twentieth century is that of a gigantic marshmallow man stomping through New York City like a sugary Godzilla nearing the end of Ghostbusters. Ghostbusters itself is one of the more interesting installments of a subgenre typically referred to as horror-comedies, a combination of the explosion of the chaos world of horror with the carnivalesque humor of the comic tradition. A film rife with horrific and apocalyptic imagery, it finds both its terror and its humor in the depiction of the end of the world occurring at 55 Central Park West, with the world destroyed not in a rain of blood and fire and terrible vengeance from above, but puffed sugar.

Ghostbusters may appear to be a frivolous work, but it can and should be taken seriously as a depiction of humor within the horrific. Humor and death are often linked, a way of dealing with the progressively terrifying world. In Bahktin’s definition of grotesque realism, he identifies the physical world of the comic with the organic transformation of death into life:

The ever-growing, inexhaustible, ever-laughing principle which uncrowns and renews it combined with its opposite: the petty, inert, “material principle” of class society…The grotesque image reflects a phenomenon in transformation, an as yet unfinished metamorphosis, of death and birth, growth and becoming (24).

Death and the comic concept of renewal are inextricably linked; the world must end in order to be reborn. If we examine Ghostbusters through this lens, as a serious if also comic examination of death and comic transcendence through parodying and satirizing the end of the world itself, we may elucidate how this film, and other horror-comedies, defy the ineluctable nature of death by literally making fun of the repressive as well as the repressed.

Much horror functions as an expression of the repressed in the form of the monster; much comedy too expresses the repressed in the anarchic vision of the comedian or comedians. The difference is usually that the figure of horror, the monster, is a frightening manifestation of the repressed psyche, a figure that represents gender, class, race or sexual difference that the homogenous society represses. Comedy, by contrast, revels in anarchic expression, the libidinal impulses of the central comedians and their subversion of the social order. Both genres represent eruptions of the chaos world in anarchic visions. They are festive arts that challenge the social order through the creation of fear, laughter, or both.

True festive art…is an art that ultimately celebrates communality, much as any festival does…Festivity is not opposed to depth of meaning. As Bakhtin has noted, certain truths are only available through festive art. A worldview that sees a split between body and spirit limits the value of material existence (Paul 71).

When comedy and horror function in tandem with each other, they form a deep expression of what Paul here defines as a ‘festive art:’

The seriousness of this festivity…resides in the extent to which it inverts the most deeply rooted values of Western culture (71).

In exposing and then making fun of what is most terrifying, we acknowledge the fear, but also the absurdity of the fear. The Ghostbusters participate in a carnivalesque rebellion and joy in destruction usually only open to the monsters of the horror genre. Acting from within the system, the Ghostbusters succeed in subverting the system.

Despite the at times conservative, masculinist nature of its discourse, Ghostbusters inserts its central figures into a material world that refuses to acknowledge the spiritual. The spiritual then manifests itself as something only they can control because they are capable of recognizing its existence. The Ghostbusters have a complicated relationship to the ghosts they capture. They are essentially agents of repression, ‘exterminators’ who arrive to trap and confine the libidinal impulse. Neither the first film nor its sequel address what happens to the ghosts once they are captured, or the moral and ethical complexity of keeping these spirits within a ‘containment unit.’ The three original Ghostbusters are all white middle-class males, educated and, at the opening of the film, acting from within institutional confinement. They are representatives of scientific materialism, all doctors dedicated to the trapping of spirits. They act at the behest of the ruling establishment to arrive and exterminate (or trap) the manifestations of the return of the repressed. In doing so, however, they subvert the system in acts of anarchic destruction.

Athough initially functioning within the establishment, the Ghostbusters come to reject and be rejected by that establishment. The first fifteen minutes of the film sees them confront their first ghost, and lose their jobs at the university. Although they may be educated, they nonetheless appear as working class figures. They are self-described exterminators, essentially the ghost police, identified as such by the uniforms that are janitorial jumpsuits. They live in an old firehouse somewhere on the Lower East Side; their car is a refurbished ambulance. Their names are also indicative of class, religion, and immigrant background: Peter Venkman, Raymond Stantz, and Egon Spengler (Harold Ramis). Throughout the film various members of mainstream WASP society treat them with confusion, contempt and downright aggression. The villains of the film are all representatives of the WASP establishment: the dean at their university (Jordan Charney) and Walter Peck, a representative of the EPA (William Atherton). The establishment, although willing to exploit them, is equally unwilling to trust them. When they are called in, it is unwillingly and with evident embarrassment on the part of the Mayor (David Margulies). The Ghostbusters stand in a liminal position between the libidinal spirits they trap and the material establishment world.

Many of the ghosts in Ghostbusters function as manifestations of libidinal impulses, grotesque representations of the natural body in their obsessions with food, sex, violence, and destruction. Freed from their material existences, the spirits are also free to indulge the libidinal impulses they were perhaps denied in life. The most obvious of these is the famous ‘Slimer’ character, actually referred to as ‘Onionhead’ in the screenplay, the first ghost the Ghostbusters trap (Aykroyd 78). A floating yet apparently physical being—he comes into physical contact with Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) and ‘slimes’ him—his libidinal drive is to eat and drink. He first appears consuming plates of food from a service cart, later eating food from a banquet table and drinking bottles of wine that pass through his spiritual body. His spirit haunts the ‘Sedgwick Hotel,’ an upper class establishment. The Sedgwick is the site for the ultimate in class gluttony. Onionhead consumes the remnants of apparently lavish meals; he invades a sumptuous banquet hall and devours food and wine. We may perhaps view Onionhead as the libidinal manifestation of upper class gluttony, come to revenge itself, a literal return of the repressed.

The Ghostbusters tracking and trapping of Onionhead bears closer scrutiny. They are out of place at the Sedgwick, arriving noisily, dressed outlandishly and carrying gigantic pieces of equipment on their backs. The hotel manager (Michael Ensign) seems uncomfortable in their presence and asks them if everything can be taken care of ‘quietly.’ Harold Ramis remarks, in the DVD commentary, that the Ghostbusters were conceived as Marx Brother-type characters and the Sedgwick Hotel sequence bears this out (Ramis, ‘Commentary’). Comically out of place, they are working class figures in an upper-class setting. Incapable of controlling their equipment, they destroy a large section of the hotel, burning holes in walls, harassing guests, and causing destruction in the banquet hall. They find humor, if not total release, in this destruction:

Ray: I think we’d better split up.

Egon: I agree.

Peter: Yeah, we can do more damage that way.

In hunting down Onionhead, they destroy a chandelier, a full bar, break several tables, glasses and china, and light things on fire. At the conclusion of the scene, they charge four thousand dollars for the destruction they have caused, threatening to replace the captured spirit if they do not get their money.

Whether wittingly or unwittingly, the Ghostbusters actually cause more destruction than the ghost they hunt. Like the Marx Brothers, the Ghostbusters are dependent on the mainstream for their livelihoods; no longer employable as scientists, they have recourse to the working class milieu, but in doing so are able to take revenge, monetary and otherwise, on the system that has rejected them. They may be dependent on the system itself to support them—they certainly do not try to exist outside of it—but they are able to subvert it from within. What is more, they make the system pay for its own destruction. This joy, the humor that comes out of not only Onionhead’s gluttony but the destruction brought about by the Ghostbusters, succeeds in a satiric carnivalesque rebellion that allows the rejected, now working class figures to begin a process of destruction from the inside out.

A third of the way through the film, the Ghostbusters are joined by another liminal figure, this one legitimately working class: Winston Zeddemore (Ernie Hudson). Winston acts as a fourth, lesser figure in the triumvirate, a sort of Zeppo to the Ghostbusters. Winston is the only solidly working class figure in the film. He has not lost his class in the way that the other three have. The fact that he is a black man complicates issues of race, although none of the other characters make reference to his blackness. Certainly he is demarcated as different from the other three, in class and race background, and in the part he has to play. The casting of Eddie Murphy, the initial choice for the role, might have resulted in a more equitable balancing of comedy and dialogue between the four men, but as it stands, Ernie Hudson probably has the least input of any character in the film. Harold Ramis even admitted that the Winston character went through numerous changes and that because they were so concerned about including an African-American and avoiding charges of racism, they created him as almost too good (Ramis, ‘Commentary’).

Winston is one of the few characters to express religious leanings and the first to indicate the possibility of their actions being tied to the apocalypse:

Winston: Do you remember something in the Bible about the last days when the dead rise from the grave?

Ray: I remember Revelation 7:12. ‘And I looked, as he opened the Sixth Seal and behold there was a great earthquake, and the sun became as black as sackcloth and the moon became as blood.’

Winston: And the seas boiled and skies fell.

Ray: Judgment Day.

Winston: Judgment Day.

Ray: Every ancient religion has its own myth about the end of the world.

Winston: Myth? Ray, has it ever occurred to you that maybe the reason we’ve been so busy lately is that the dead have been rising from the grave?

This is the most serious exchange in the film, one of the few instances when the comedy ceases for a moment and the possibility of the actual ending of the world becomes clear. By placing the apocalyptic prophecy in the mouth of the most liminal character, a true representative of the working class and the oppressed, the film ties its apocalyptic imagery to the place of the repressed. Winston stands for practicality (‘Ray, when someone asks if you’re a god, you say YES!’) and a spiritual otherness that counterbalances the intellectual superiority of Egon, the naïveté of Ray and the showmanship of Peter. The mixture of practicality and spirituality can sometimes smack of stereotyping—of course the black man heralds the coming apocalypse! —despite the concerns of the (white) writers to avoid such stereotypes. Winston at some level fulfills the stereotype of the ‘magical negro,’ whose connection to the spiritual world is more attuned than that of the white mainstream figures. His practicality, however, subverts and complicates this archetypical characterization. He acts within a more complex racial climate that, while it does not fully equalize the role of the black man, avoids making him a stereotype. For the film at least, blackness is a non-issue. Given the apparent liminality of the other three Ghostbusters in terms of class and ethnic background, the film does not easily fall into a black/white binary. Winston actually has the last line in the film, and while this does not fully restore him to equality with the other three, it does at least give the most practical and most liminal figure the last word. Far from viewing Winston as the ‘black servant’ of the white males, he acts as a down-to-earth character that represents the blending of practicality and spirituality that the others lack (Paul 128).

Femininity and sexuality figure into the film in a similar complicated manner. Dana (Sigourney Weaver) essentially plays the ‘straight man’ to the three Ghostbusters, particularly Peter. Again taking the Marx Brothers comparison, she is Margaret Dumont or Thelma Todd. Peter pursues her, erotically, flirtatiously and even in a somewhat predatory manner. He maintains control of sexuality and the male/female binary until the evil spirit Zuul possesses her. Her possession transforms her first into a libidinous and sexual character, then into a demon dog. When Peter arrives at her apartment, he is confronted with not the somewhat reticent woman who has resisted his slightly sarcastic and lascivious advances, but a full-blown sexual creature, complete with make-up and wind-blown hair. His reaction is discomfort, if not downright terror. Still, the relationship is not as simplistic as it first appears. What disturbs Peter is not only Dana’s suddenly intense sexuality; it is also that her sexuality is uncharacteristic of her. It does not necessarily represent a danger to him, but a danger to her.

Dana: I want you inside me.

Peter: OK. No, I can’t. It sounds like you’ve got at least two people in there already. Might be a little crowded. C’mon, why don’t you just quit trying to upset and disturb Dr. Venkman and just relax?

Unwilling to take advantage of the situation and actually sleep with her, he rejects her advances and asks to ‘speak to Dana.’ Peter, who makes sexual advances to almost any female throughout the film, is at a loss and disturbed when met with a manifestation of feminine libido. Simultaneously, however, he acts in the kindest, most moral way possible. He declines to take advantage of her, recognizing that the woman clinging to him is not Dana at all, but a spirit inhabiting her body. He finds recourse to jokes, as he does throughout the film, but the scene takes on a new level of discomfort and nervous energy. Far from the playful tone of sexual innuendo that has been exchanged between them from the beginning, Dana now makes almost violent sexual advances towards him. Peter, for all his talk, is not a sexual predator. His reaction is to try to get help and locate the ‘real’ Dana within the false one. Their relationship will return to a masculine/feminine dialectic in the end, but I would argue that in this case Peter succeeds in recognizing the ‘real’ Peter that would not take advantage of a possessed woman. His sexuality, despite his lasciviousness, does not extend to actually engaging in illicit or dangerous sexual acts. He can only make jokes.

Sexuality continues to be a central concern of the film. The Ghostbusters are associated with a strictly masculine paradigm, represented in the plethora of phallic symbols and innuendo. The guns they use to capture ghosts, the ever-present PKE meter that Egon likes playing with, and lightly comic jokes about Twinkies and ‘crossing the streams’ punctuate moments of sexual humor throughout the film. At the same time, Ray and Egon are fairly clueless about women—Ray has one sexual fantasy about a ghost, and Egon cannot seem to recognize it when their secretary Janine (Annie Potts) flirts with him. Peter, as the only Ghostbuster who has any real heterosexual relationship, nonetheless becomes terrified at the first sight of a truly sexualized woman. In all of this, however, the film manifests an awareness of the tropes it plays with.

The apocalyptic narrative of the film comes into play through the realm of sexuality. Gozer, the one who will bring about the apocalypse, can only be summoned through the sexual union of the Gatekeeper and the Keymaster. The Gatekeeper in this case is a woman, the Keymaster a male, calling attention to the sexual puns inherent in those titles. The Keymaster controls the phallic; the Gatekeeper controls the feminine. This references the familiar euphemism for female genitalia as a ‘gate’ that needs a phallic male ‘key’ to unlock it. Films such as The Devil’s Advocate (Warner Bros., 1997) and Rosemary’s Baby (Paramount, 1968) found their apocalyptic ideology within the necessary joining of masculine and feminine, resulting in the end of the world or the coming of the Anti-Christ. Ghostbusters subverts these recognizable tropes of the apocalyptic by making them comic. Even before the appearance of Mr. Stay-Puft, the apocalypse is something to laugh at. The coming together of the hypersexual Dana as Zuul and Louis Tully (Rick Moranis), the nebbish accountant, as Vinz the Keymaster is a humorous image. Dana stands head and shoulders above Louis; she literally sweeps him off his feet. Their embrace is extremely stylized; as they kiss the wind blows, the music swells and the camera swirls around them. The shot has a self-conscious camp aesthetic, although it avoids total parody. What in other films is a terrifying, erotic moment becomes a piece of comedy.

Although Winston and Ray engage in the most serious elucidation of the coming apocalypse in their brief scene, the full explanation for what has happened in Dana’s apartment is given by the most intensely intellectual figure in the film:

Egon: It’s not the girl, Peter, it’s the building…The architect’s name was Evo Shandor; I found it in Tobin’s Spirit Guide…After the first World War, Shandor decided that society was too sick to survive. And he wasn’t alone; he had close to a thousand followers when he died. They conducted rituals up on the roof. Bizarre rituals, intended to bring about the end of the world, and now it looks like it may actually happen!

Peter (singing): So be good, for goodness sake! Somebody’s coming…

The scene occurs in a holding cell after the Ghostbusters have been arrested. Surrounded by prisoners, Egon gives a speech about the sickness of society and the ritualistic desire to bring about the end of the world. Despite the seriousness of his speech, he keeps a steady smile on his face as he speaks. The smile, the apparent enjoyment he has out of explaining the coming apocalypse, elucidates the strange festivity, the comedy of death. The world is going to end; Egon smiles and Peter sings. When they appear in the Mayor’s office, they again perform a comic apocalypse:

Ray: Real wrath of God type of stuff. Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies. Rivers and seas boiling!

Egon: Forty years of darkness, earthquakes, volcanoes!

Winston: The dead rising from the grave!

Peter: Human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together, mass hysteria!

Coupled with the Biblical imagery are the comical aspects of ‘dogs and cats living together.’ While the apocalypse does not seem a completely banal occurrence in this scenario, the comedy of the situation, the gallows humor of laughing at the end of the world, permeates the entire scene. The subversion of the usual somber tone of apocalyptic films and imagery transforms the apocalypse itself into a farce, something not to be taken seriously.

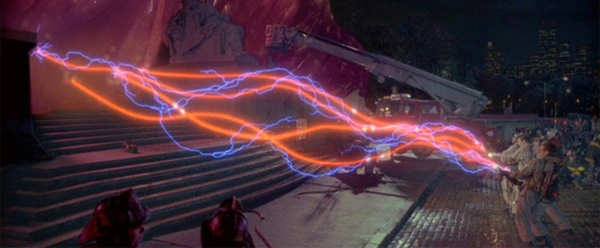

The final sequence of the marshmallow apocalypse brings together the manifestations of the repressed, libidinal impulses, and the dialogues of phallicism and gender into a final festival moment of comic destruction. Supported finally by the establishment (including the Army, the Police, the Fire Department and the Mayor’s office), the four working class figures arrive to stop the end of the world. The crowd that stands to greet them and cheer them on is a multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-classed crowd, come together in festival to watch the Ghostbusters save the world. Gozer manifests itself initially as a woman, played by supermodel Slavitza Jovan, a deliberately sexualized figure who threatens to destroy the Ghostbusters. Recovering from her initial attack, the Ghostbusters return to (comical) phallic symbolism:

Peter: Got your stick?

All: Holding!

Peter: Heat ‘em up!

All: Smoking!

Peter: Make ‘em hard!

All: Ready!

The deliberate phallicism of the dialogue again relates the ‘wands’ of the Ghostbusters proton packs to not terribly subtle phallic imagery. They attack Gozer, but fail to conquer her. Instead, she demands that they name the ‘form of the Destructor,’ making the choice about what it is that will destroy them. Here the sexualized figure, un-subdued by phallic masculinity, turns to a chosen apocalyptic image; only the chosen image is a marshmallow man.

Mr. Stay-Puft is the final and most potent manifestation of the repressed libidinal psyche, actually coming from the mind of one of the Ghostbusters. Ray justifies his choice by saying that he tried to think of something that ‘could never destroy us.’ The apocalypse, then, is going to be wrought not by a sexualized supermodel, or a prehistoric demon dog, but a walking wad of puffed sugar. The apocalypse thus manifests itself as an empty figure of fun, a sugary concoction that stomps around midtown Manhattan. The ironic nature of the apocalypse becomes humorous and painful:

‘Sometimes it’s hysterical irony and sometimes it’s a painful irony. Life has all of these contradictory feelings and contradictory results…We’re always shut off from pure joy’ (Ramis, as qtd. in Spitznagel 4).

The festivity of the apocalyptic scenario in Ghostbusters acts as a manifestation of painful irony: the world is about to end, but how ironic that it will end in a rain of marshmallow. Mr. Stay-Puft is also a corporate logo, a symbol of consumerism, and therefore a post-modern construction within the cinematic milieu. Ray does not think of just any harmless character, but a harmless corporate character. The film proposes destruction based around a literally rampaging consumer product.

The Ghostbusters defeat Mr. Stay-Puft by doing what has already been stated as dangerous—they cross the streams from their proton packs, apparently reversing the polarity of Gozer’s door and destroying Mr. Stay-Puft. If we carry through the phallic symbolism already related, the Ghostbusters comically and sexually unite, establishing a homoerotic masculine paradigm that ends with the destruction of first the sexualized Gozer (who is nonetheless also asexual—she need not be male or female), and the freeing of Louis and Dana back into ‘normal’ sexuality. Mr. Stay-Puft erupts in a rain of marshmallow, covering everyone below. There is no denying the apparently orgasmic and masturbatory imagery this scene involves, as the four Ghostbusters combine their phallic instruments, resulting in an explosion of white foam that covers them all from head to foot. Emerging from death, the Ghostbusters establish a new, highly masculine paradigm that nonetheless allows for comic rebirth. The city and the world are saved through an orgasmic explosion of male sexuality.

This is the ultimate transformative moment of comedy, as the bringer of death appears in a comic form, and death itself explodes in an abject bodily function. The ending of the world is satirized through Mr. Stay-Puft. The film satirizes the union of sex, death and destruction through the establishment of a figurative male union and a New York covered in sugar/semen. Although the images and thematics of Ghostbusters are exceptionally serious, taking on the end of the world, the problems of normative sexual relationships and the eruption of the chaos world in the form of enjoyable but damaging libidinal excess, the comedy of the film subverts the tropes from within, by acknowledging their terror, but also their humor. In the end, Mr. Stay-Puft explodes and the Ghostbusters save the day, destructors themselves from within the system. The marshmallow apocalypse is averted, but we are all still covered in sugar.

Aykroyd, Dan and Harold Ramis. Making Ghostbusters, ed. Don Shay, Columbia

Pictures Industries, New York: 1985.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky, Indiana University

Press, Bloomington: 1984.

Hallenbeck, Bruce G. Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History 1914-2008,

McFarland & Company, Inc., London: 2009.

Meehan, Paul. Cinema of the Psychic Realm: A Critical Survey, McFarland & Company,

Inc., London: 2000.

Paul, William. Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy, Columbia

University Press, New York: 1994.

Ramis, Harold. ‘Commentary on Ghostbusters’ in Ghostbusters, dir. Ivan Reitman,

Columbia Pictures: 2005.

Spitznagel, Eric. ‘Interview with Harold Ramis’ in The Believer, March 2006.

Tudor, Andrew. ‘Why Horror? The Peculiar Pleasures of a Popular Genre’ in Horror,

the Film Reader, ed. Mark Jancovich, Routledge, New York: 2002.

Wood, Robin. ‘The American Nightmare: Horror in the 70s’ in Horror, the Film Reader,

ed. Mark Jancovich, Routledge, New York: 2002.

Hackford, Taylor (dir). The Devil’s Advocate, Warner Bros., 1997.

Polanski, Roman (dir). Rosemary’s Baby, Paramount, 1968.

Reitman, Ivan (dir). Ghostbusters, Columbia, 1984.

Ghostbusters II, Columbia, 1989.