This month, TCM has introduced “Reframed,” a series dealing with problematic classic films that seeks to interrogate their issues with racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of bigotry. The series featured Gone with the Wind, a film that has been discussed for years, really, to the point where some critics have suggested retiring it from circulation except as a study tool. But much of the discussion around Gone with the Wind, both on the program and via TCM’s Twitter feed, did not actually address the film’s racism, romanticization of slavery and the slave-owning class, or the mythologizing of the antebellum South. Rather, the series seemed to treat Gone with the Wind as kinda racist but not, well, that racist.

Gone with the Wind has been a thorn in the side of classic film discourse for some time. It’s an explicitly racist film based on an even more explicitly racist book, but much of the racism is either subsumed or ignored in favor of the resilience of Scarlett O’Hara, the romance of Scarlett and Rhett, the conflict of Ashley and Melanie, the tragedy of the burning of Atlanta and the destruction of Tara. It’s a melodrama, a romance, and much public discussion ignores the fact that slavery is papered over as, at worst, an unfortunate occurrence (not to mention that one of the characters joins an early version of the KKK). This is about Scarlett and Tara and Rhett, right?

It is, of course, about them, and that’s one of the big problems with Gone with the Wind. The film is indeed a natural heir to Birth of a Nation, made even more insidious by its romantic, Technicolor packaging. It is a romance and tragedy of the Old South in a way that manages to skirt all the real issues, and to pose the white, slave-owning class as tragic heroes and heroines.

McDaniel broke a barrier and that shouldn’t be ignored. But she broke it for a playing a racist caricature during a deeply racist period in Hollywood—she even had to have special permission to attend the (segregated) Oscar ceremony, because the Ambassador Hotel didn’t admit Black people. The fault is not McDaniel’s—after all, these were the major roles available to Black women in the 1930s, and she finds greater nuance in Mammy than one might expect. But her Oscar has become a touchpoint for Hollywood to pat itself on the back: “We gave a Black woman an Oscar in 1939! We were always progressive!”

Which brings us back to TCM. TCM, for a long time, was among the major voices of classic films. Through them, an entire generation was introduced to movies that were other unavailable or under-shown. With streaming, access has changed, expanding in some ways and contracting in others. But TCM remains a major player, both in terms of the films they show and in terms of the way they frame the films they show. More than most, TCM has formed the way that viewers understand the pop cultural canon of classic film. And for a long time, they have included Gone with the Wind, among others, in that canon.

Most of the films TCM has chosen for their Reframed series are unfortunately predictable: The Jazz Singer, Gone with the Wind, The Searchers, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Gunga Din, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, Tarzan, Rope, The Four Feathers…many, though not all, have been discussed, debated, interrogated, and dissected by critics, scholars, and viewers for years. Most of these, in fact, have long been considered problematic classics, for their racist caricatures, narratives of racial or sexual violence, use of blackface, redface, or yellowface, or often extreme stereotyping. What’s more, TCM has regularly shown these films, without commentary or debate, and often without context. These films, in fact, have formed the pop cultural cinematic canon to which TCM has contributed.

It’s interesting that here we have some of the most blatant racist or sexist caricatures, yet other films are not included in the mix: Lawrence of Arabia, which features Alec Guinness and Anthony Quinn as Arabic characters; Flower Drum Song, which features a large cast of Asian American actors but has drawn criticism for stereotypical depictions and the use of Japanese American actors as Chinese American characters; South Pacific or Mutiny on the Bounty, both romanticized visions of colonialism and the exoticization of Polynesian women; or the oft-debated Hallelujah or Cabin in the Sky, films with all-Black casts directed by white men. TCM has chosen no films that deal with orientalism, exoticization, or fetishization, no films that vilify abortion, no films that punish female sexuality. No films to make viewers truly uncomfortable or to address the more insidious nature of racism, sexism, homophobia, and bigotry. No films, really, that force the viewers to interrogate what they’re seeing, beyond the obvious.

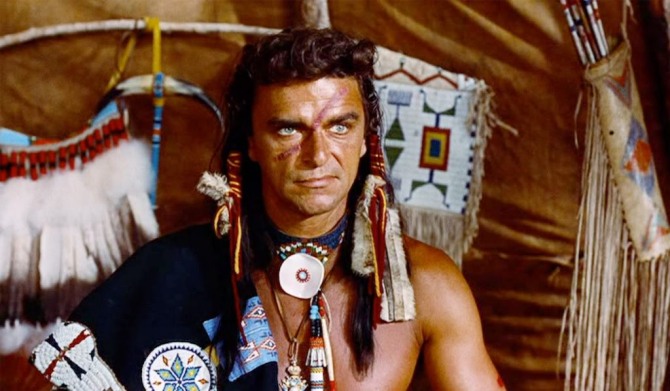

In fact, almost all of TCM’s Reframed series are either blatantly problematic—white people playing non-whites, songs about rape and abduction, whites murdering American Indians—or include more minor elements or one-off scenes that make them problematic (such as Swing Time, which I presume was chosen because of the “Bojangles of Harlem” number, in which Fred Astaire appears in blackface). These are, in other words, easy films, not films to force the viewer (or the network generally) to confront insidious stereotypes and problematic plot devices. It’s easy to look at Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and be horrified. It’s also easy to dismiss him, because the character is a secondary one meant as comic relief, and therefore fairly easy to ignore. It wouldn’t be so easy to dismiss Alec Guinness playing a Japanese man in A Majority of One or Robert Taylor as the central character, a Shoshone war hero, in Devil’s Doorway.

Are those films as iconic as Tiffany’s? No. But they do provide more problematic nuances for a viewer, and the host, to interrogate. How do we deal with a film that is progressive for the time period, yet hires a white man to play a non-white character? How do we deal with racist jokes from Abbott and Costello or the Marx Brothers, characters that we’re supposed to sympathize with? For that matter, let’s talk about the problems contained within To Kill a Mockingbird and its depiction of racism, classism, and sexual abuse.

TCM rarely, if ever, steps outside already canonized cinema, which means that they ignore or minimize the contributions of actual PoC, female, queer, and other marginalized creators. They made a point of showing Mark Cousins’s documentary Women Make Film last year, but rarely show films actually made by Dorothy Arzner, Lois Weber, Alice Guy Blache, or other pioneering female filmmakers. A brief scan of their March listings includes a number of films directed by Michael Curtiz, Delmer Daves, Lloyd Bacon, Powell and Pressburger, Alfred Hitchcock, and even Gene Kelly. Agnes Varda appears to be listed once, at two in the morning, and seems to be one of the few female filmmakers being shown during Women’s History Month. They’re addressing racist stereotyping in white Hollywood, but rarely show the films made by Oscar Micheaux, Spencer Williams, or Paul Robeson. Their films currently showcased on HBOMax include approximately thirty with major Black characters—out of over five hundred films. While “Reframed” implies that TCM is looking to do better, they’re not addressing their own role in systemic oppression, the shaping of the narrative around predominantly white mainstream films, or in the valorization of films that maybe are not as essential as we’ve been led to believe.

It’s good that TCM is examining, albeit a bit late, the problematic underpinnings of many classic films. But we also need to interrogate the way in which TCM has shaped this pop cultural understanding of the cinematic canon in the first place, how they have helped make films like The Jazz Singer and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers so iconic to later generations. They have long considered Gone with the Wind and The Searchers essential films. Far from truly interrogating the films they already show, they never go the extra step to actually show different kinds of films, to step outside canonical frameworks and make films like Within Our Gates, The Blood of Jesus, Working Girls, Hypocrites, The Adventures of Prince Achmed, or A New Leaf the true, new essentials of the canon. No, the essentials are still the same. And they’re not, like, that racist, right?

William Byron

This was spot on. Thank you for articulating this so, so well.