When Anton Yelchin died in 2016 his death resonated with film audiences who barely knew him. Maybe it was because he was just 27, maybe it was the tragic freak nature of his death, or maybe, as director Garret Price lays out in the awe-inspiring documentary Love, Antosha, maybe it was because just by looking at him we knew he was a great person, a loving son, and a talent whose inner fire burned faster than his body would allow him. Love, Antosha isn’t a sad film, although audiences will feel sad watching the heartfelt anecdotes from the people who loved him the most, but instead is meant to inspire, uplift, and ultimately prove that Yelchin was better than anybody could have dreamed of.

If Yelchin’s origins weren’t true you’d assume they were the work of a Hollywood movie. His parents, Victor and Irina, fled Soviet-era Russian in order to give him a better life, giving up their career as successful ice skaters to raise their son in the San Fernando Valley. In fact, Yelchin and his parents are the trio that runs throughout the film, with one never doing anything without the other. Price, given unprecedented access to Yelchin’s house, his diaries, and his home movie footage, doesn’t just tell a story about a boy growing into a man, but a son and the parents he loved. There’s so much love between the trio that your heart will burst on that alone. Hearing Yelchin sing songs dedicated to his mother or apologize for having an argument with her isn’t just affecting because of his demise, but because he’s a better child than any of us.

Price and the myriad of talking heads that run the gamut from Jodie Foster to Jennifer Lawrence never eulogize or sentimentalize the man they knew. His long-time friends share stories of traveling the world and getting into trouble, Chris Pine hilariously recounts Yelchin’s weekend excursions to sex dungeons to snap interesting photos, and Kristen Stewart opines about him being the first person to break her heart. These moments always feel authentic, not tragic but nostalgic.

The group isn’t just remembering a friend, but a moment of freedom when they believed anything was possible because Yelchin was there. Of course, the most bittersweet moments are with Yelchin’s parents. His mother recounts finding a condom in his jacket, giggling to herself and, for a moment, finding some comfort and levity. Yelchin’s own words and poems are read by Nicolas Cage which, on the surface, might sound like a distraction but Cage reads Yelchin’s letters with such love and respect. His tone of voice actually sounds generic, as if he understands the goal is to respect the boy known as Antosha. You can almost hear Cage break down at certain points, particularly toward’s the film’s conclusion, finally unable to hide the pain he feels.

A key component of Love, Antosha’s narrative is Yelchin’s fight with cystic fibrosis, a disease many of his co-stars and directors learned about while filming this. Yelchin’s parents deliberately hid his diagnosis for several years of his life, leading to frustration and conflict within him. As he got older, the documentary shows Yelchin’s own fears of dying young, knowing that the median age for CF patients is 37.5; Yelchin was pushing 30. It’s painfully ironic to hear from one of Yelchin’s best friends that in his final moments he was unable to breathe, a fear he’d had since learning about his disease. And yet Yelchin took that idea of borrowed time and ran with it, creating his own art instead of waiting for someone else to make what he wanted to star in.

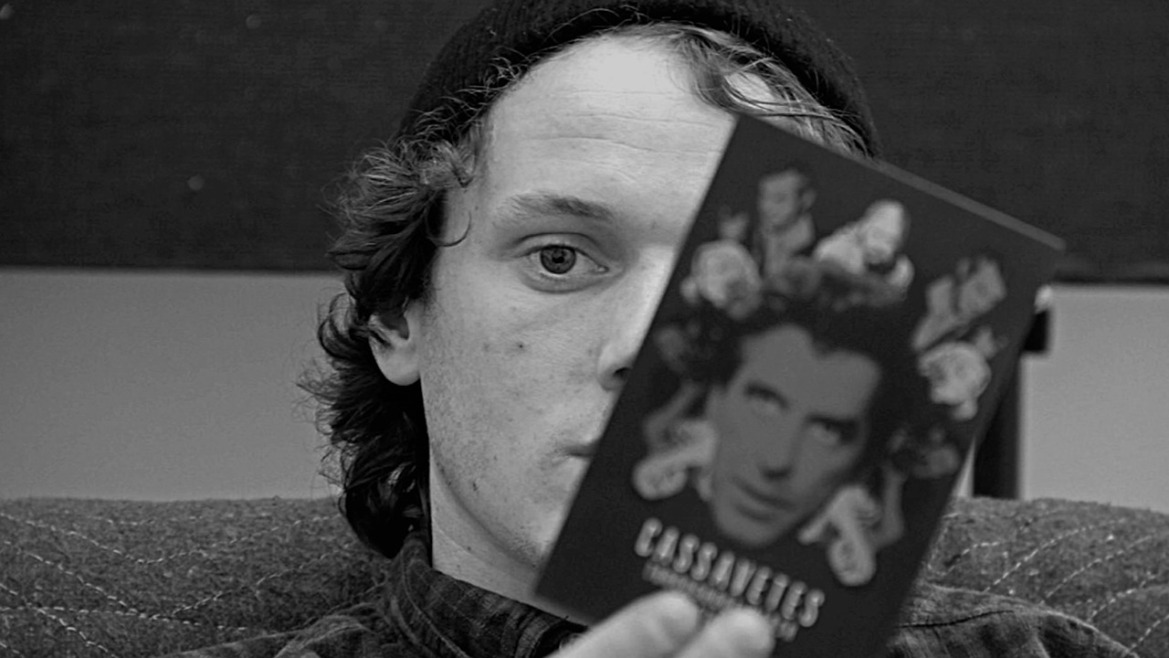

On top of the typical talking heads Price showcases several of Yelchin’s short features. Yelchin was a prolific filmmaker, documenting and making his own movies practically from infancy. It’s one thing to watch clips of a young Yelchin capably sail through working alongside Anthony Hopkins, but it’s another to see proof that Yelchin was ready to go behind the camera. His love for film was fostered at a young age his father recounts, showing him Taxi Driver, and from there Yelchin was a regular at repertory screenings. His lists of movies, with in-depth analysis, and the bevy of DVDs in his house, illustrate a man who literally loved all aspects of cinema.

Love, Antosha is filled with such reverence, appreciation, gratitude, and, yes, love. Yelchin was a beloved son, and though it’s painful to hear that his parents visit his grave daily, the documentary shows it’d be hard to have it any other way. The Yelchins, as a unit, are the best of people. It sounds cheesy, but Price makes the argument that the people Yelchin knew (and the audiences he entertained) were made better because of him, and we should all be thankful.

Love, Antosha hits limited release August 2nd and expands August 9th.