With the exception of the early films of Alfred Hitchcock, British silent film often gets short shrift when discussed in comparison to the pantheon of other Western cinemas. And it is true that British film heavily borrows from the other cinematic traditions – many directors from the silent era, including Hitchcock, worked under German directors, borrowed techniques from Germany, Russia, and America, and would go on to Hollywood and comparatively greater fame. The British film industry was small but active during the pre-war years, and many silent films still survive that showcase the complexity of contemporary British filmmaking. One of the best is also one of the latest: A Cottage on Dartmoor, a melodramatic thriller made in 1929 by one of the greatest British filmmakers of the period.

A Cottage on Dartmoor is was the final silent film directed by Anthony Asquith, who would go on to greater fame for his versions of Pygmalion, The Winslow Boy, and The Importance of Being Earnest. The story opens with an escaped convict (Uno Henning) fleeing across the moors and breaking into a lonely cottage where a young woman Sally (Norah Baring) tends to her small child. When she sees him, she cries out “Joe!” snapping the viewer back to when the two worked in a salon together, Joe as a barber and Sally as a manicurist. The rest of the narrative encompasses what led Joe to prison, and them both to a cottage on Dartmoor.

A Cottage on Dartmoor bears a striking resemblance, both in style and substance, to the silent films of Alfred Hitchcock, who would release both versions of Blackmail the same year. Dartmoor is a psychological thriller, going deep into the emotional and mental states of its characters through montage, cross-cutting, and reaction shots, and filled with an array of sometimes comedic and sometimes grotesque secondary characters to complicate the central narrative. The use of montage here is sophisticated, employed for comedic effect as well as the creation of psychological suspense, as when Joe mentally compares a man he’s shaving to a chicken clucking.

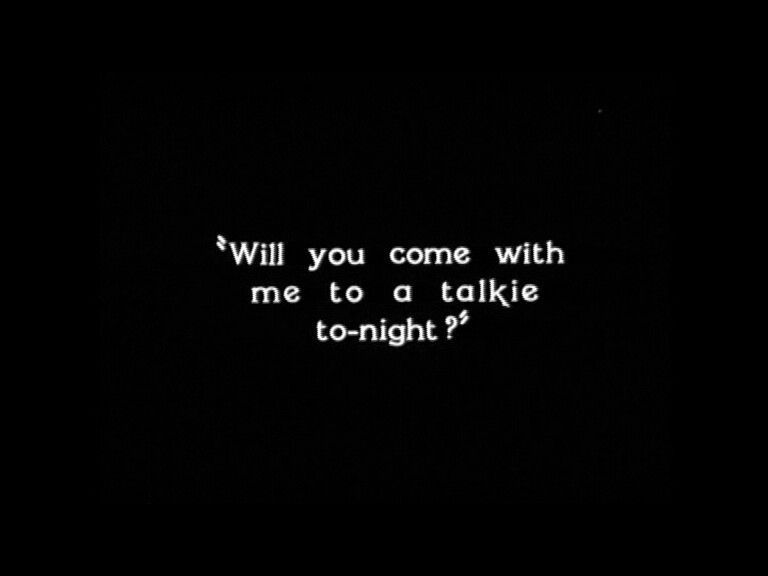

The film turns on Joe’s obsession with Sally and his jealousy of any man who comes close to her. But it’s also about the power of the image, the way that images shape experience, and what is seen and unseen. Joe’s jealousy is wrapped up in his perception, as he mistakes Sally’s kindness for love, and her honest flirtation with other men for coquetry. Asquith uses all the techniques at his disposal to showcase just what the image can do, from depicting a character’s thoughts, foreshadowing their desires, and creating suspense in both love scenes and in scenes of violence .But it does more than that – it communicates a sense of sound as well, as when Sally plays the piano for Joe, or a pit orchestra provides the soundtrack to an (unseen) Harold Lloyd film. The image is a potent force here, made more so when one realizes that the actors are all from different countries – this was the Swedish Henning’s only English film – something which was common in silent cinema and would be made impossible with sound film.

A Cottage on Dartmoor is a defiant tribute to silent film, then very much on its way out, and what pure cinema could accomplish. And it’s a fantastic work of art for that, exciting, entertaining, humorous, an entertaining melodrama laden with sharp commentary on cinema as a whole. This might be one of the last hurrahs of silent cinema, but what a way to go.

A Cottage on Dartmoor is available to stream on Kanopy and YouTube.