Ida Lupino has gone through a re-evaluation recently, lifting her from the ranks of a female director occasionally referenced for a single contribution to cinema to her rightful place as a major auteur. This is thanks in part to a renewed focus on female filmmakers and the efforts of publications, critics, and film distributors like Criterion and Kino Lorber to bring new attention to women who have been marginalized or forgotten for their contributions to cinema. In a new box set comprising four of Lupino’s films, Kino Lorber spotlights the “Mother of All of Us,” a director and writer who shaped the nature of film noir and the “women’s film” in ways that are still provocative, ground-breaking, and entertaining.

The Blu-ray box set features four of Lupino’s films, newly restored and with a number of special features, including commentary tracks by film scholars and an extensive essay by Ronnie Scheib arguing for Lupino’s status as an “auteuress.” Scheib’s essay is a must-read—a well-argued presentation of Lupino’s work centering on the four films and including extensive references to Hard, Fast, and Beautiful and Outrage, which are not included in the set. The commentary tracks are likewise essential for feminist film critics and those interested in Lupino’s output, offering differing perspectives on her work and her influence.

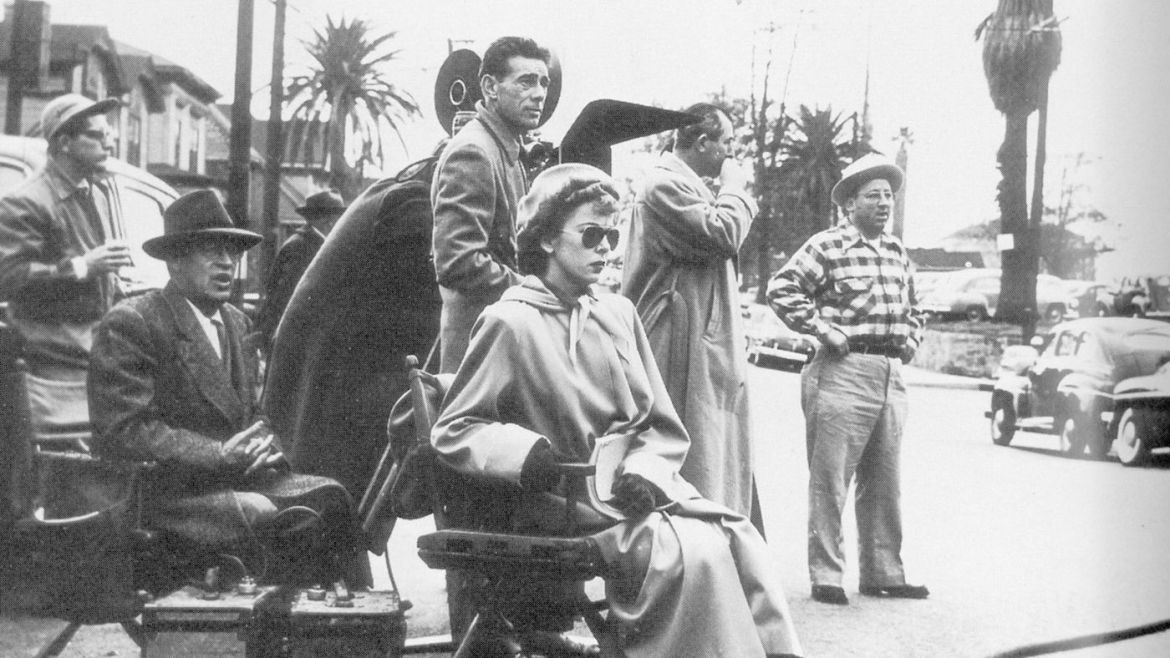

Lupino’s most famous film is still The Hitch-Hiker, a tense film noir about Gil and Roy (Frank Lovejoy and Edmund O’Brien), two buddies on a fishing vacation who pick up a psychopathic hitch-hiker (William Talman) on the run from the law. Most of the film comprises the interactions between the three men in the claustrophobic closeness of the car, or in the just as claustrophobic deserts between California and Mexico. The film brings scrutinizes the concepts of masculinity and power in a film noir context, but one of the more interesting undercurrents of The Hitch-Hiker is the relationship between the Mexican and American authorities, and specifically the use of Spanish-speaking characters to drive the narrative. There are whole scenes in Spanish, without subtitles, and the Mexican authorities are the heroes as they pursue the villain across the border. While this is far from the focus, the construction of Mexican authorities and Spanish-speaking civilians as the main friends of the two hostages stretches beyond the more usual contemporary vilification of Mexico and Mexicans as self-interested or, at best, apathetic to crime.

This folding of gender and cultural considerations within a melodramatic context is one of Lupino’s hallmarks. The Kino set also includes two of Lupino’s “women’s issue” films: Not Wanted, a narrative about unwed motherhood (which I reviewed several weeks ago on DameStruck), and Never Fear, one of her earliest and most personal films. Never Fear speaks clearly to Lupino’s position as an auteur in her own right—she wrote and directed the film on a topic close to her lived experience, as it deals with a dancer (Sally Forrest, who also appears in Not Wanted) and her experience of polio. Lupino herself contracted polio in 1934—though she largely recovered, she later said that it was the realization that as an actress she was primarily valued for her body’s abilities that led her to want to write and direct. Never Fear’s focus is also on a woman who depends on her body for her livelihood, and much of the film is about her evaluation of her self-worth and the psychological experience of her illness. Never Fear and Not Wanted act as an excellent double-bill as narratives of female psychology and valuation of self as they interact with a culture that puts exceptional restrictions and requirements on women. (The same could be said for Outrage, about rape and its aftermath, unfortunately not included in this collection.)

The Bigamist rounds out this set with another topical social investigation couched under melodramatic constructs. It’s the story of a married man (O’Brien again) who falls in love with another woman (Lupino) and marries her without divorcing (or telling) his first wife (Joan Fontaine). This is the sort of story that could veer into either lurid or moralistic territory (or both), but the film deftly navigates this by constructing sympathy for all the characters, revealing layers of social mores, sexual and emotional desires, and how basically decent people can wind up doing wrong things. It’s a surprising film for its sympathetic portrayal of all involved, and is the only film in the set to feature Lupino herself in a role (as the second wife, no less).

Kino has once again crafted an excellent box set with a sampling of four films by a filmmaker who deserves greater scrutiny beyond her single, male-centric noir. Lupino’s films dig into the social constructs of gender, feminity, and masculinity, and the effect of those constructs at both an individual and cultural level. As a woman and an actress working at the height of Hollywood’s patriarchy, she carved out a place for herself behind the camera at a time when female filmmakers were seldom taken seriously (when they directed at all), and told stories that were daring and provocative in ways that male directors of the period would have been incapable. Lupino has more than earned herself a place in the pantheon of great directors, and this set gives puts to rest Andrew Sarris’s attempt to consign her to the dustbin of film history. The Mother of All of Us has finally taken her seat.