Priscilla Dean was a major silent film star, an action heroine and comic actress, now often forgotten, though she worked with Lois Weber, Phil Rosen, and even Laurel and Hardy. Many of her major works, like Weber’s The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, and the early serial The Grey Ghost, are now lost, perhaps accounting for Dean’s slide into comparative obscurity. But Kino-Lorber is changing with the Blu-ray release of three of Dean’s films made with Tod Browning at Universal. Browning’s films feature Dean as a hardboiled antihero, a woman who often ignores her humanity in favor of cynicism and survival, but in the last reel, rediscovers her humanity and acts both as a heroine and a romantic lead.

Dean’s roles with Browning give to the lie to what contemporary reviewers usually associate with the women of silent film as damsels in distress or weak, “soft” roles. Dean always saves herself, perhaps with some small assistance from the leading man…if she feels like it.

Outside the Law

Outside the Law is Browning’s first collaboration with Dean. Here she’s a tough-as-nails jewel thief Molly Madden, whose father is framed for murder by Black Mike Sylva (Lon Chaney), a thief who wants to marry Molly and take over her father’s business. Convinced of her father’s innocence and out for revenge, Molly teams up with one of Sylva’s boys, Dapper Bill (Wheeler Oakman) to double-cross the thief. Naturally, Molly starts fall for Dapper Bill and has to choose between her desire for vengeance and the promise of a more normal life.

Outside the Law frames a heroine in a role often designed for a hero—betrayed by her colleagues, Molly seeks vengeance for her family and herself. Forced into hiding, however, Molly begins to soften both to the idea of a family life and to a life outside of crime—thanks to the combination of Bill and a little boy who lives next door to them. The shift is marked not because it pushes Molly into a performance of “acceptable” femininity, but because it is usually the kind of shift that a male hero will undergo via a woman’s influence. In this case, it’s the man who relates well to children, the woman who thinks kids are, at best, annoying, and who only belatedly begins to soften towards the idea of family and motherhood. The film is hyperfocused on Molly’s arc and her battle with Black Mike, culminating in a massive (and shockingly bloody) fight between Black Mike’s mob, Dapper Bill, and Molly.

Drifting

Drifting is a 1923 melodrama starring Dean as an opium smuggler in Shanghai who wants to go straight. When her partner Jean (Wallace Beery) mucks things up for her, Cassie Cook (Dean) heads to a remote village where the opium is grown to discover whether or not a new mine overseer (Matt Moore) is a government agent in disguise.

Drifting is inherently an Orientalist fantasy and there’s little that the film does to subvert that, relying on Chinese caricatures and stereotypes to flesh out the story. But while the majority of the Chinese characters are played by white men in yellow-face, there are a few narrative and visual shifts that make things, if not acceptable, at least more complex. Almost all of the background characters, including a group of children, are actual Chinese actors, providing some verisimilitude. At the center is a young Anna May Wong as Rose Li, the daughter of one of Cassie’s partners, who is also in love with the mine overseer. While Rose Li could have been a caricature, Wong’s already rivetting screen presence imbues her with greater nuance and sympathy. She dislikes Cassie but doesn’t fully understand her father’s crimes, and becomes one of the major actors in the climax of the film.

As with Outside the Law, Dean plays a “bad girl” who more or less tries to go straight via the dual influences of a decent man and a child. Drifting also complicates this somewhat—after Cassie attempts to leave Shanghai and fails, she’s disenchanted by the efforts of the law on the one side and her criminal compatriots on the other, driving her towards a cynical embrace of the drug trade. The depredations of opium are depicted via one of Cassie’s friends, an addict, and the violence and fear in which the people of the village live. But ultimately Cassie is not made over by a man lecturing her, but her own inherent humanity and heroism. It’s notable that in this film, as in Outside the Law, the women are the saviors, while the men are either villains or, in this case, aggressive do-gooders who almost cause a genocidal war.

Drifting culminates in a spectacular set piece involving a deliberately set fire and gang war, and is perhaps the strongest argument yet for Browning’s silent work and abilities as a director. While we’re used to seeing Browning’s films as investigations of the supernatural, his silent work showcases a broader sensibility for action, suspense, and pacing, and Drifting is an excellent example.

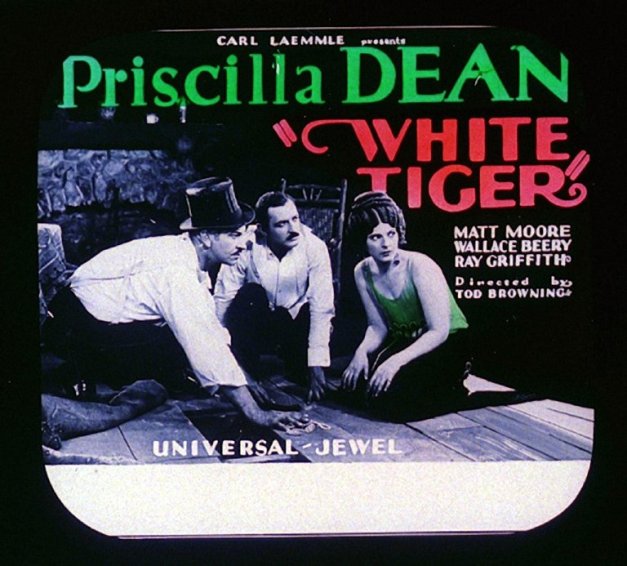

White Tiger

The final entry to this set of Browning/Dean releases is White Tiger, a film that places Browning in more recognizable—for the contemporary viewer—uncanny territory. Dean is Sylvia Donovan, whose criminal father and elder brother were (supposedly) murdered when she was child. She’s raised by Hawkes (Wallace Beery), the man who (unbeknownst to Sylvia) informed on her father. But her brother also survived—now a small-time con man known as The Kid (Raymond Griffith), he comes across Sylvia and Hawkes while running a new scam in which he operates an “automaton” who plays chess for money. Unaware of who he is, Sylvia and Hawkes team up with The Kid to travel to New York, pretending to be Italian aristocrats in order to use the automaton to gain entry to the homes of the wealthy. Things predictably begin to unravel as The Kid starts to suspect that Hawkes is the man who murdered his father, and Sylvia starts to fall for a wealthy socialite.

White Tiger is perhaps the weakest of the three (complete) films included here, possibly due to a poor print and some evident elisions and missing frames. But the criminals’ actual scheme isn’t terribly clear, and the fact that The Kid doesn’t recognize Hawkes at first seems like a bizarre oversight. The final act, however, with the three criminals holed up in a small cabin, gradually becoming mistrustful of each other, is a wonderful stroke of claustrophobic paranoia and indicates more than any of these films the direction Browning’s career will eventually take him.

The disc that includes Drifting and White Tiger also includes a fragment of The Exquisite Thief, yet another reminder of the films that have been lost (even those made with relatively well-known directors and stars).

These films provide a unique insight into Browning’s style as a silent filmmaker and, more importantly, Priscilla Dean’s undoubted screen presence as a strong, capable woman. As with all Kino releases, the quality of the discs is second to none. Hopefully this signals a continued desire to bring more films out of contemporary obscurity, and especially to cast light on the undoubted brilliance and range of female stars in the silent period.