Long before he became the Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock was a workaday filmmaker whose output mostly consisted of comedies, melodramas, literary adaptations, and chamber pieces for British International. Kino’s new box set, Hitchcock: British International Pictures Collection, includes five of these films, a sampling of Hitchcock’s early work that stretches beyond his better-known thrillers. The beautifully restored set includes four silent films, Champagne, The Ring, The Farmer’s Wife, and The Manxman, and the early sound melodrama The Skin Game. These films provide a unique and essential insight into Hitchcock’s development as a filmmaker far outside the genre for which he eventually became known.

Many of Hitchcock’s earliest works have been dismissed as mere steps towards him becoming the director who, in turn, became his own genre. Hitchcock himself often dismissed his early works in interview, saying that they were programmers or studio assignments. But this set makes an excellent argument for these films as more significant, important works, not throwaway assignments that eventually led to Hitchcock’s “real” career. Champagne opens (and closes) with a striking POV shot through a champagne glass, reminiscent of the German Expressionists (for whom Hitchcock worked as a young title card writer) and predating more famous shots in Spellbound and Notorious.

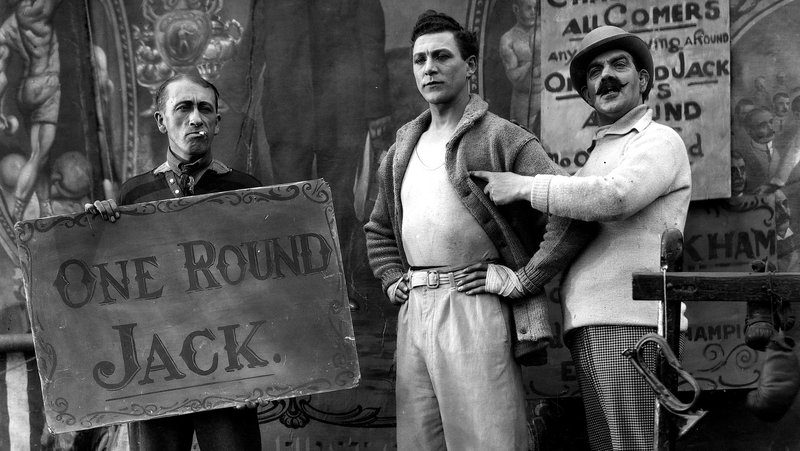

Hitchcock’s interest in suspense is already in full flower, but here he applies his tenets to non-thriller films, constructing strangely sinister meanings underneath otherwise innocuous images. The Ring contains one of the most intense suspense sequences Hitchcock ever filmed, but it’s not about a bomb under the table – it’s about a husband’s discovery of his wife’s infidelity. The Skin Game features a tense auction sequence, emphasized by rapid camera movement and rhythmic cuts; Champagne builds focalization in a series of complex point of view shots, interweaving reality and the character’s imagination until the elements blur together. The Manxman slowly increases the tension as a love triangle moves towards violence and suicide. The constant shifting of perspective, the use of the camera eye to manipulate audience sympathy, even the extent to which the camera alters our perceptions of the characters as it shifts perspective—these have already come to fruition here.

These are hardly student films or exercises meant to develop filmmaking chops. They have the assurance of an already mature, complex filmmaker, experimenting with elements of expressionism via Murnau, Weine, and Lang in a distinctly British setting. The silent films in particular are showcases for what Hitchcock considered “pure cinema” – a substantial lack of title cards means that the narrative, characterization, and emotional beats develop via the image, the suspense built through crosscutting, montage, and superimposition of frames. Revelations are held back from the audience until the conclusion of a scene, the suspense building through what we can discern (and assume) via the actors faces.

The relaxed nature of British censorship of the period (as compared to post-Code censorship in Hitchcock’s move to America) means that Hitchcock can explore issues of sexuality, alcoholism, rape, and infidelity. But more interesting is the way in which these elements are filtered through female characters, as in Champagne and The Skin Game in particular, as Hitchcock develops multifaceted women that demand audience sympathy via focalization.

Alfred Hitchcock was a great genre filmmaker, but he was also a great filmmaker, period, as this box set so clearly and beautifully attests. All five are gorgeously, lovingly restored, as we expect from Kino. The extra features include new scores and audio commentary from film scholars , as well as relevant excerpts from Hitchcock’s interviews with Truffaut. But the real stars are the films. These films have been primarily seen in scratchy public domain prints, so it is a rare and important treat to see them so delicately and beautifully treated.

While Hitchcock would transition more fully into the crime and thriller genre by the time he left Britain, these films also question what we consider a “Hitchcock film.” After all, this is a filmmaker who continued to make comedies (Mr. and Mrs. Smith, The Trouble with Harry), melodramas (Under Capricorn), and courtroom dramas (The Paradine Case) well into his American period. These are not outliers to be discarded or footnotes to his career. They are true “Hitchcock films.”