Defenses of the First Amendment have been tossed around quite a lot recently. Roseanne Barr’s supporters attempted to claim that critics violated First Amendment rights after ABC decided to cancel her show over her racist comments. White men start shouting about First Amendment rights whenever someone disagrees with them on Twitter. Many of the people who complain about First Amendment violations don’t know what those rights even mean, much less what consists a violation of them. So it would do well for all of us to see the documentary Boiled Angels: The Trial of Mike Diana, showing at Fantasia 2018, for a look at what government-sanctioned censorship and First Amendment violations actually look like.

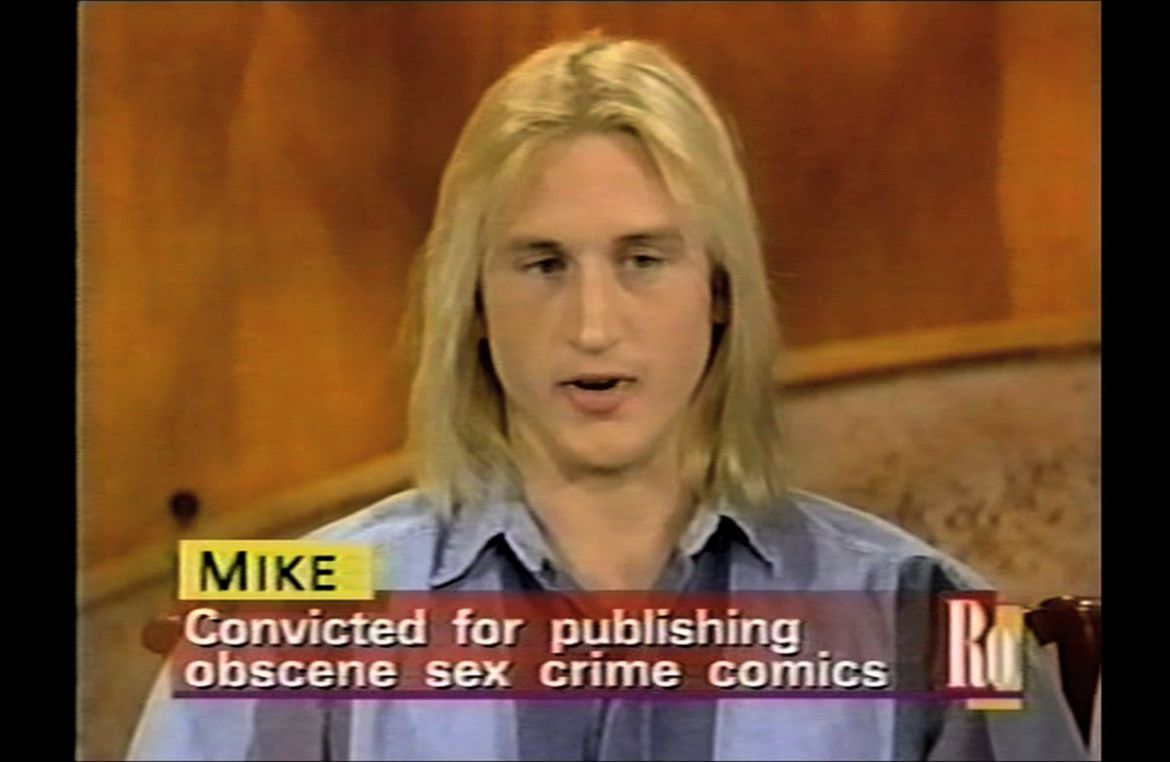

Mike Diana has gone down in history as the only American artist ever convicted of obscenity charges in his art. Diana was part of the growing zine culture in the 1980s – a world of underground comics, hand-drawn and usually printed in small batches, that were either sold via head shops or directly from the artist. The zines grew out of the underground comic culture of the 1960s and 70s and were often in violation of what’s considered good taste: extreme depictions of sex and violence, from bestiality to pedophilia to mutilation, things that would not pass the “Comics Code,” and that were intended solely for adult consumption. Diana began producing his own zine Boiled Angel, which was intended to be as shocking, graphic, and offensive as he could make it. When police officers got ahold of the zine, they took it to the Florida state attorney’s office, who in turn filed charges of obscenity against Diana. The resulting case became national news, and ended with Diana’s conviction.

Boiled Angels takes us on a parallel journey, explaining the nature of underground comics and the rise of zines as a result of the Comics Code, enacted in 1954 as a reaction against horror and crime comics deemed “dangerous” to America’s youth. Like the cinematic Production Code, the Comics Code governed what could and could not be shown in mainstream comics, driving anything else underground. In tandem, the film tells Diana’s story, from his childhood in Geneva, NY, to his family’s move to Largo, Florida, where he began to make horror movies at home, and finally to draw the comics that would eventually send him to court. Much of the film is told in Diana’s own words, in somewhat stilted (and possibly scripted) interviews that describe his interest in horror and the underground comic world, and his personal views of his admittedly extreme and graphic art. Like many artists who focus on extreme violence, Diana claims that he was reacting to the world around him, to the violence on the television news, and to the horrors enacted by the adult world. He explains his use of sacrilegious imagery – scenes of children being sodomized by priests or crucifixes – when he describes learning about the scandals in the Catholic church at a young age. The comics, he says, are outpourings of anger and terror, raised to such extremity that they become comical, so wild that it’s difficult to take them seriously.

But the police in Florida did take them seriously. The film interviews a number of people involved in the trial of Mike Diana, including prosecutor Stuart Baggish, who made it a mission to bring Diana up on the charges of obscenity; Diana’s defense lawyer Luke Lirot, fellow artists from around the country, and even several protestors from concerned mother groups who believed that Diana’s work was the product of a deranged and possibly devil-possessed mind. Most interesting are the varied reactions to Diana’s art – Baggish is evidently horrified by it, while others (reporters, artists, filmmakers, and writers) find it at worst gross or distasteful, but not particularly evil. And the film doesn’t exactly ask the viewer to judge Diana based upon the art he produces, shocking though it is. What it asks is whether or not that art should be censored.

Boiled Angels has a crazed punk sensibility – it’s narrated by former Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra, and there’s an edge of mockery in the depiction of the forces of law and order who seem to make Diana an Exhibit A for the corruption of youth in America. The film undoubtedly believes that Diana’s case was a miscarriage of justice, but ample time is given to the prosecutor’s arguments that Diana did indeed fulfill the requirements of obscenity, and that prosecuting him on these grounds was legally correct. The film doesn’t shy away from showing some of the offending pages of Boiled Angel in detail – depictions of rape, pedophilia, bestiality, mutilation, and dismemberment abound, which to most viewers is, at best, repellent, and at worst sickening. But that’s also not the point. The point is…is it art?

An undercurrent running through Boiled Angels is the belief that any artist who can create something so violent and disturbing must be himself violent and disturbed. Diana was actually suspected of being the Gainesville student murderer, entirely based on the similarity between certain scenes drawn in his zines and the scenes of the real-life murders. But he’s shown as a quiet, innocuous man, both in contemporary interviews and in interviews during his trial, and he claims that he doesn’t like real-life violence, and was disturbed from a young age by killing or by stories of real-life pedophilia and incest. Comics are not real life – they are extreme depictions of the world in which we live, filtered through the artist’s mind and pen. The idea of art being indicative of the real-life mentality of the artist recalls a number of contemporary arguments that we cannot separate the art from the artist, that anyone who produces scenes of violence must be violent in themselves.

Boiled Angels questions just how far we can and should take that mentality, revealing a remarkable and fairly recent miscarriage of American justice, an attack on First Amendment rights and the right of the artist to draw, provoke, and even sicken. The question is not do we like the art, but whether or not that art should be censored and its creator fined and imprisoned for producing it. Can we excuse an attack on First Amendment rights because the art is personally repellant to us?

Boiled Angels: The Trial of Mike Diana opens on July 14.

Episode 42: Sorry to Bother Dames – Citizen Dame

[…] is at Fantasia Fest and reviewed Boiled Angels: The Trials of Mike Diana and The […]

Blood & Flesh: The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson is a Tribute to Low-Budget Film (Fantasia 2019) – Citizen Dame

[…] features a few interesting (and bizarre) documentaries mixed in with their genre films. Last year, Boiled Angels: The Trial of Mike Diana was among my favorite views at the festival. At Fantasia 2019, it’s Blood & Flesh: The Reel […]